By Beth Yahp

IT’s March 7, eve of the elections. I’m at my usual morning teh tarik corner shop in Bangsar, the New Straits Times [NST] under my arm, making my way to a table out back where I can eat with elbow room, watch people and catch up on the news. It’s my favourite morning activity, neighbourhood workers bustling in for breakfast or old Uncles coming in for a kopi and chat, sleepy-looking students thumbing through the papers like me. A typical Malaysian scene. My teh arrives hot and beautifully frothy.

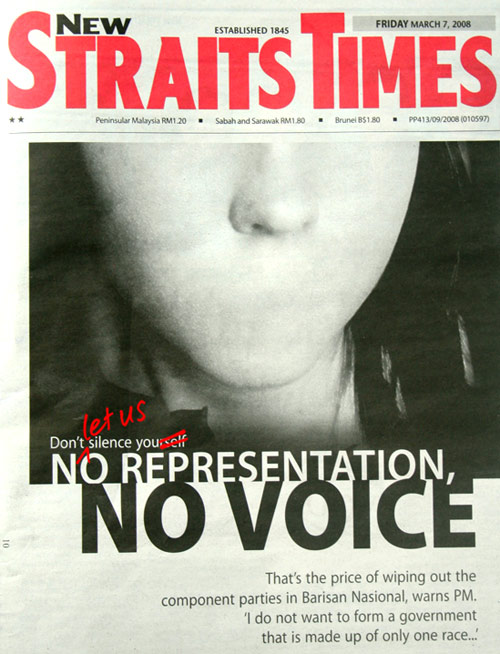

I unfold my NST, looking for the day’s big news. I involuntarily jump back from the front page: has a Korean hantu [ghost] like Ju-On suddenly been bussed in to Malaysia? Or a spectre from the Twilight Zone? The front page blazes a doctored photo to people my nightmares, and today it’s headline “news”. I know that by now I shouldn’t be, but I’m too shocked to finish my tea. Without having noticed, I’ve mechanically stuffed most of my tosai into my mouth, no recollection of chewing or tasting.

I’ve scanned the front page for news, but today there isn’t any. As well as the schlock-horror photo of the young woman in ghostly black-and-white with her mouth erased, there’s an ad for getting “total control of your finances”, another for NST online, and a politically-motivated parable masquerading as news. I jump out of my chair. Although I should be used to it by now, I squirm at the feeling I’ve been cheated. I want news! That is, objective, informed reportage, telling both or more sides of any story – not a full front page advertorial. I wonder how much it cost, in actual ringgit or in kind.

I know, in Malaysia, that this is a dangerous feeling. I need to walk it off. But as I’m leaving, I pass an old regular, a white-haired Uncle, sitting serenely, newspaper beside him, with his glass of tea. He looks so calm and collected, on this eve of “Tomorrow’s the Day”, that I’m desperate for some of it to rub off. I plomp myself in front of him, boldly. “Uncle,” I begin, “what’s your opinion…?”

He’s a little alarmed and suspicious at first, but then we settle into a conversation that ranges from the mood of this elections (“different”), to everyone’s right to make money (“even MPs, but they should help others too”), to why it’s “impossible” for us to move beyond race politics in Malaysia, to the definitions and dangers of freedom and democracy, to what our newspapers were like in his youth (also “different”), to the importance of asking “Why?” (and why Malaysians today won’t do it).

I show him the front page of today’s paper. “It’s to sell papers la,” Uncle says. “To attract people, they look at it, they wonder why. If you put a semi-naked woman on the cover, this evening cannot find any copies… They will put anything violent, sexy, to attract people… but not information.”

“Why, Uncle?”

“If we know too much, it will lead to turmoil.”

“What do you mean, Uncle?”

“Yes, it will lead to turmoil… if we know too much, if we use it to distort people’s mentality. Men are unequal. If I’m more educated, I can convert your mentality… that’s what top leaders do, they can incite us internally.”

We both look at the picture. “I think I got incited, Uncle,” I tell him. “I got scared when I looked at it. It looks to me like hantu…”

Uncle runs his finger over the warning from our PM, about “not want(ing) to form a government that is made up of only one race…”: something we presume he’ll have to do if we force him, by “silencing ourselves”, by not voting BN’s racialist component parties in.

“It’s impossible,” Uncle shakes his head. “The government can’t form with only one race, because other races contribute too. And one race cannot form government, it’s impossible… because even one race, they are divided. MCA is divided. MIC is divided. Each has their own ideas and their own traditions, different kinds of Chinese, different kinds of Indians.”

“In Malaysia today,’ he adds, after a sombre pause, ‘we cannot call ourselves Malaysians. The government will never let us be called Malaysians… we are only Malaysians when we go abroad. Here we are Indians, Chinese, Malays.”

“Why can’t we be both?” I suggest. “Chinese and Malaysian, Indian and Malaysian, Malay and Malaysian?”

“Girl, listen,” Uncle leans forward. “It’s impossible to go beyond race politics because then we will be one nation… and this will lead to people’s power, all people will come together as one, then it is difficult for the government, they can be toppled. Look at the Philippines, everyone thinks they are Filipino first, so they go out on the streets. Here it is divide-and-rule, people are divided. We are all different races. Every human being has emotional feelings, but we depend a lot on race… Race is so big because the top politicians make it so, they practice divide-and-rule.”

The NST’s front page straddles the space on the table between us. Uncle studies it. “Ya, it looks like hantu,” he concedes. I have an idea, one to cheer myself up with. “Uncle, maybe the wise editors put it there to remind us of hantu!” I blurt. “That there are many hantus among us, especially around election time!”

Uncle looks stunned, then he and I burst out laughing. When we stop, he muses: “There are always two ways of thinking about something…” He taps the photo. “I didn’t see it that way.”

“Isn’t that called democracy, Uncle?”

“Democracy,” he says, almost disdainfully. He shakes a finger at me. “People here have stupid, wrong ideas about democracy – that you are free, you can do whatever you like. That will lead to turmoil… Full democracy is not practised anywhere in the world. Full democracy becomes very violent, when everyone can voice out whatever we like…”

“But isn’t democracy about responsibility, Uncle, as well as freedom? That’s why we have the rule of law.”

Uncle isn’t convinced. “Democracy must be limited,” he insists. He taps the front page, reminding me: “No information.” Then he adds: “The top leaders in developing countries want you to remain stupid, they don’t want you to know anything… so we can have peace and prosperity.”

“Have they succeeded, Uncle?”

“No…” Uncle’s voice falls to a whisper. “Because of new gadgets, we are exposed to world issues… Because our press is restricted, it is only 50 per cent, 60 per cent free. If you have press freedom, you will have turmoil, the truth will come out… that’s why people go to the Internet… The papers are full of what the government wants us to read. They don’t want us to broaden our knowledge, that will be their downfall.”

Despite all this talk about turmoil and downfalls, I find myself indeed cheering up. Maybe it’s just the act of communicating with someone, of sharing a strong reaction I’ve had to something, of getting someone else’s point of view.

In Malaysia we do this when deciding on any new acquisition, when evaluating anything materially beneficial to us: a house, a job, a car. We research different sources for information about quality and performance, we compare prices and track records so we can make up our minds, knowing that we’re fully informed. Why not the same principle for feelings and ideas?

“But we are not asking: Why?” Uncle insists. “We do things because our forefathers told us so… we don’t question the purpose. We don’t ask of the politicians: What is your real purpose? What is your agenda?”

“Sometimes we ask…” I pipe up. “In the kopi tiams we ask… But maybe no one hears us…”

There’s a pause as we ponder this. Inadvertantly we look around us, to see if anyone else is listening. “There are always two ways of thinking about something,” Uncle repeats. “The idea of thinking alike must change… the idea that we are all just race. Racialist ideas must change, that we must all think alike…”

“But wouldn’t that lead to people power, and turmoil?” I cheekily ask. Before Uncle can answer a man comes to borrow his copy of The Star. They exchange quick greetings. I look at my watch.

Somehow it doesn’t matter that I disagree with the some of things Uncle says, and he with some of my ways of seeing things. It doesn’t matter that we haven’t come to any grand resolution of each and every question or problem. For instance, I still don’t believe in the inevitability of turmoil. I don’t believe we have to “hope BN wins”, as Uncle does, “so we can drink tea in peace, not be frightened of bombs in the street”.

Today, I’m more frightened by the front page of my NST, and not for the usual racialist reasons. I’m frightened by scare tactics that can throw journalistic charters and traditions out the window, that strip journalists and editors naked and ask us to stand around admiring their new clothes. Uncle and I may disagree on fundamental issues, but in Malaysia today we can still sit down and discuss things that matter to us, as we drink tea.

I stand up to leave, the newspaper folded under my arm. My initial instinct was to thrust it away from me, leave it behind, or in a garbage bin, but after talking to Uncle I realise that this newspaper still belongs to me, too. It belongs to us readers, as well as the people who plan, write and edit it. This newspaper too is a part of our historical record, not of events objectively reported, but of a phase in this country’s history of ideas and “emotional feelings”.

“Thank you, Uncle,” I smile, and he smiles back, widely. I tell him I’m a writer, here to observe the elections.

“Girl!” Uncle exclaims. “Girl, your job is to blend. To take the past, and blend it with the future, and come up with something new!”

It’s as good advice as I’ll get anywhere in the world. As I walk out of the coffee shop, I’m still frightened, and angry, but I’m smiling too. Some words are forming in my mind, and as I think them, my mouth is moving to shape them into speech.

To the people who blatantly placed an advertorial on the front page of a once grand old lady of a newspaper, established in 1845 as the Straits Times, I have this to say: Give me back my mouth. I need it, and you already have many mouths in your service.

I need my mouth not only to speak, to kiss, to grimace, to smile. To eat tosai and to drink teh. I need it to converse with wise old Uncles in the kopi shop, to ask questions and offer opinions as I listen to what they have to say.

But more importantly than all that: I need my mouth in order to live, not as a phantom, but as a human being.

Beth Yahp is an award-winning fiction writer. She is also Fiction Editor for Off the Edge, a Malaysian business/lifestyle/culture magazine.