By Danny Lim

dannylim@malaysiavotes.com

KOTA BHARU: “If you read S.H. Alattas, he wrote, ‘When you talk about Kelantan, Kelantan is a politic university’ (sic),” says Farhan Yusof, one of a quartet of locals who just happened to sit at my table at an open-air warung for tea in Berek 12, Kota Bharu . On the political beat, junior reporters tend to be tasked to get the ‘feeling on the ground’ stories that require vox pops of ‘ordinary Joes’. It’s a hit-‘n’-hope exercise that the reporters learn to ration time spent on the shy and inarticulate, and pad the article with the first voluble loudmouth they find.

These four men virtually dropped into my lap, yakking about politics with me, unsolicited. They speak with an impressive level of knowledge and a rare maturity in their analysis of politics and the surrounding issues. And after just two days in the northern state, it becomes clear to me that this is not an anomaly in everyday idle conversation.

The consensus here is that the first week of campaigning has been uncharacteristically quiet for Kelantan. “It’s been very dull,” says Farhan. Everyone’s wondering why there isn’t the hoopla and hullabaloo of elections past. Some think the parties are conserving funds for bigger bashes in the days before polling. Others feel that the people are bored with ceramahs and gatherings. With greater Internet penetration, a lot of people already more or less know what the politicians are going to talk about. It just takes one guy to be online for him to spread the news to another four or five friends. Farhan suggests other reasons: “It’s not a fair fight, one side has the TV, radio and papers, another side has ceramahs and the Internet. Knowing that, people have gradually lost interest in elections.”

Upon arriving in Kelantan, I meet Asri, a young accounting graduate currently living with his mom in Kota Bharu, helping out in her tailoring business. When he was studying in the UK, his experience of politics was when the former deputy prime minister in Tony Blair’s administration, John Prescott, met employees at the cheese factory where Asri was a part-timer. “There was no fanfare, no entourage, just Prescott talking to the workers about issues,” Asri says. Even around the town he lived then, Stoke-on-Trent, there were no posters or flags at all. The only sense there was an election was in the media where everyone was debating about issues. He is wishing we have that level of politics because it is more mature, concentrates on issues, avoids personal attacks and doesn’t waste money on flags and banners. Asri isn’t partial to any party, his interest in elections on par to watching the World Cup. He does, however, have some clear views on issues, most interestingly in his analogy of mega-project spending: “Like burning ten ringgit to produce shillings.”

Later at a family gathering in Asri’s home, his aunts and friends talk about who to vote for over cream crackers and sweetened tea. There have been so much seat-swapping and so many new candidates, they can’t tell one from the other. So, says one of Asri’s aunts, “Pakoh parti, bukan calon (Vote the party, not the candidate).” Another aunt had a lot of fun waving a Barisan Nasional (BN) flag at an event in Tumpat. “Nok seneh, pakoh BN (You want comfort, vote the BN)” she says. A neighbour retorts that they should consider the “dacing akhirat (scales on judgement day)”. Asri’s cousin comes up with a compromise: “Oghe Kelate kena ajar BN, beri BN menang, bawok duih belaka, lepahtu ambik Pah balik. (The Kelantanese should teach the BN a lesson, let the BN win, let them pump in all the money, and then bring back PAS after that).”

In my experience of casual Malaysian conversations, opposing political supporters tend to keep their counsel, or restrain themselves from gung-ho pronouncements. In Kelantan, BN and PAS (and to a lesser extent Parti Keadilan Rakyat) supporters can debate about politics, show their colours and still revel in each other’s company. There is a sense that as much as the Kelantanese enjoy politics, they consider themselves above political loyalty, and are loathe to let the parties define their identity. “The Kelantanese are politically-savvy, even the coffee shop talk is intelligent,” says Farhan. “Kita pikir lain, tapi kawan tetap kawan (We may have different thinking, but friends are still friends).”

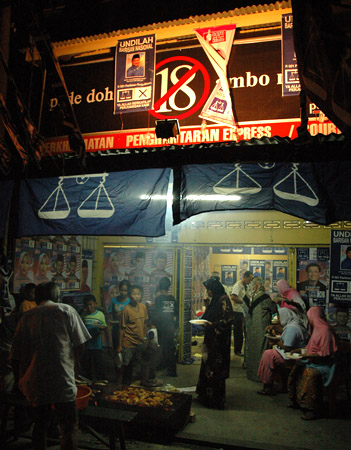

In another warung meeting, PKR campaign worker Din shares chicken satay with Ramli, a former independent candidate in the ’70s and ’80s, and now an Umno supporter. “I ask the people of Kelantan to destroy PAS!” says Ramli. “Eighteen years in power, and they’ve done nothing. They only talk about Islam, but don’t do anything.”

In another warung meeting, PKR campaign worker Din shares chicken satay with Ramli, a former independent candidate in the ’70s and ’80s, and now an Umno supporter. “I ask the people of Kelantan to destroy PAS!” says Ramli. “Eighteen years in power, and they’ve done nothing. They only talk about Islam, but don’t do anything.”

“Pade doh!” (Enough!) is the BN’s slogan to take over Kelantan, and Din feels that the words really strike a chord. “Even Umno people don’t deny that the mood around the country is that people want change,” says Din. “So they’ve also tapped into that mood here [where PAS is the incumbent].” Din feels that the fact that a lot of PAS candidates are still the same old leaders betrays a succession problem within PAS, and it’s something that the BN has played up with another slogan “Ore Mudo, Mudoh Baso“, which Din translates as “Young people, easier to meet or help”. “This is targeted at the fence-sitters, who are mostly young voters,” says Din.

This old and young factions in PAS is also noted by Farhan. “Kelantan was a major centre of Islamic scholarship about 200 years ago. Many of us are descendants of religious teachers. But now you have those educated in religious schools in Kelantan and those who are educated outside the state, and overseas. [The latter] are educated in a more modern ideology, which values development.” He cites the shrinking of old voters as one of the reasons why PAS lost Terengganu in 2004, and has lost a lot of ground in Kedah.

“The orang lama PAS (older faction) has a slightly fanatic mentality,” says Farhan. “They emphasise prayer and Quran scholarship. The orang baru (new faction) are more modern. They still value prayer, but they want personal development that is more than just that.”

Development has been the BN’s primary mantra in its Kelantan campaign. It is, however, not an easy sell to the Kelantanese. “Development-wise, we’re ok,” says Farhan. “Considering that this is an opposition-controlled state, we’re doing quite well actually. In concept, we all want development. But we have to look at the technicalities of how it is executed. If we have a sudden rush of big projects, then property prices will go up. Then the price of goods will go up. Then there will also be more corruption, which inflates the prices of the projects, and so on.”

On the fate of Kelantan come polling day, the straw poll has been very inconclusive. A passenger that I share a kereta sapu (unlicensed taxi) with claims that “Kelantan hijau kukuh, hijau sejati. Yang lain hijau tiruan, macam Terengganu. (Kelantan is solid green, authentic green. The rest are fakes, like Terengganu).”

Ramli is adamant that the BN should win, but is too unsure to say who will win. Nominally a PAS supporter, Farhan, however, believes that the BN will take the state this time by a slim margin, according to his own objective ‘reading’ of voter sentiment. “Less voters will come out because they have no confidence in the voting process,” he says. Farhan’s take on the underlying factor in the Kelantan campaign: “This is really the Pak Lah versus Najib election. They’ve come to Kelantan five times over the last two months. If Pak Lah comes, Najib comes next.”